Project Collaboration Toolkit

The Project Collaboration Toolkit is a practical guide designed to help project managers across the UK engineering construction and industry sector communities enhance collaboration and improve project delivery performance.

Share by email

These details will not be saved anywhere or used for any purpose other than sending this one-off email

Project Collaboration Toolkit

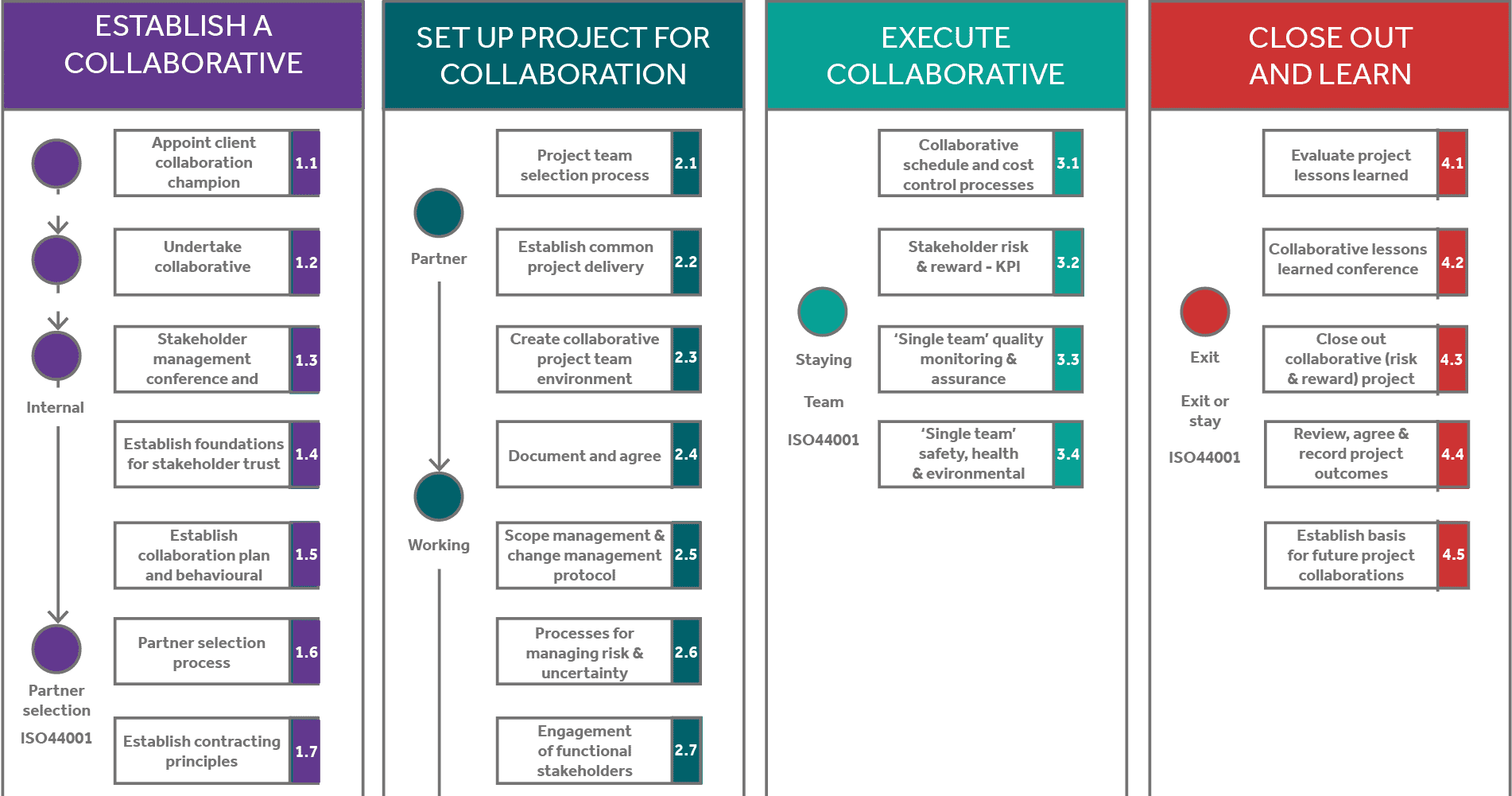

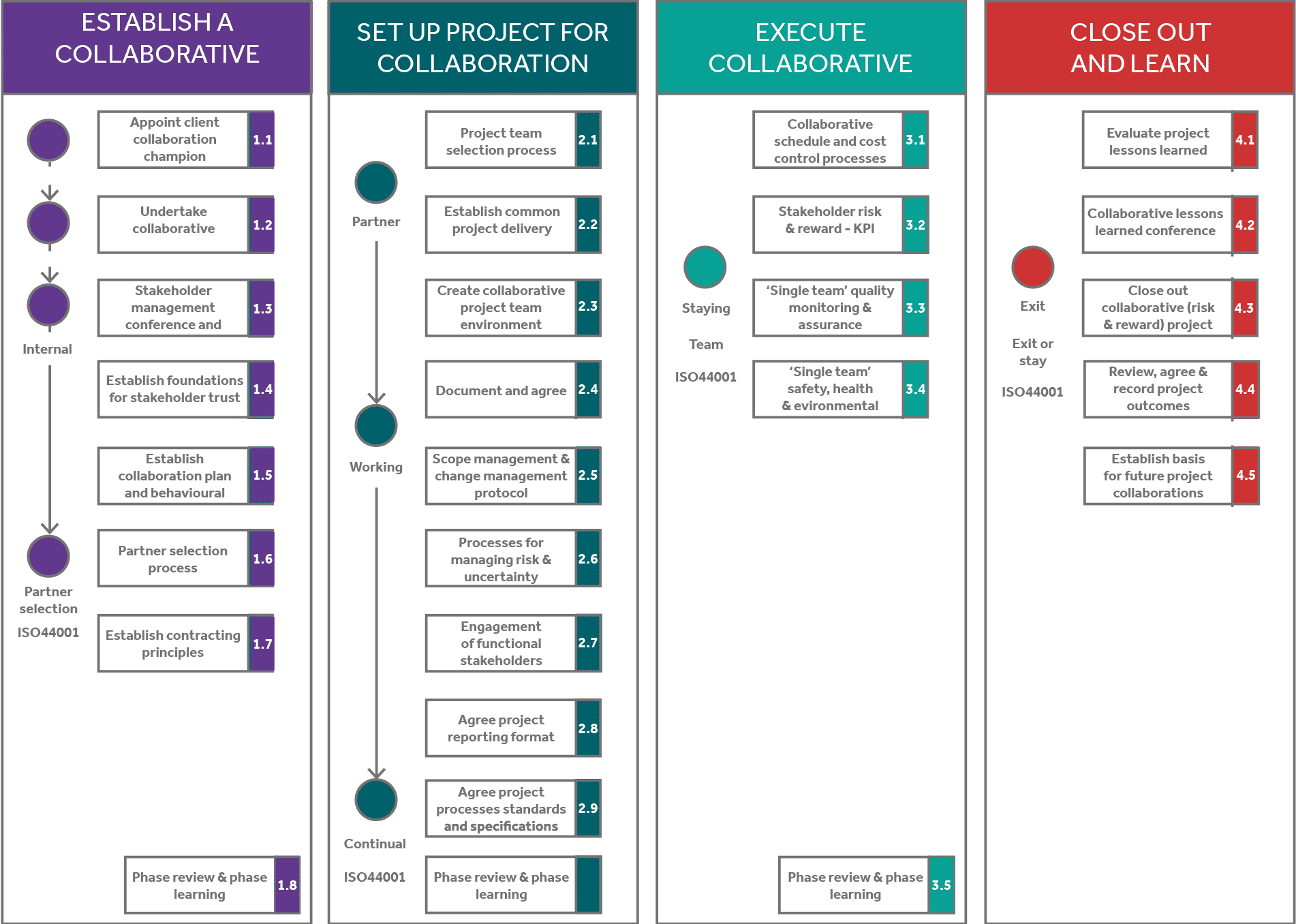

The ECITB’s Project Collaboration Toolkit (Edition 3) supports collaborative working relationships across the engineering construction sector. The toolkit offers advice and guidance to companies looking to work together more efficiently. The toolkit shares industry best practice and guides clients, contractors and other supply chain organisations on joint working.

Originally designed for the offshore oil and gas sector, the toolkit has now been used on several projects where pooled resources and shared skills and expertise have improved efficiency and provided a wide range of benefits.

The ECITB Project Collaboration Toolkit provides guidance on actions to achieve, or improve, collaboration. It assumes organisational leadership and support for a collaborative project strategy are in place and that continuous organisational development and support for the people involved will be provided throughout.

Download the Project Collaboration Toolkit

Why? The case for collaboration

The ECITB Project Collaboration Toolkit has been used on a number of major projects. These projects of different scope, size and complexity, have delivered a range of different experiences and benefits through the adoption of a collaborative delivery strategy. The outcomes and experiences of these projects have been captured in the case studies on this page.

A collaborative environment should be about the best people delivering the right work in an open and communicative environment, where risk and reward is shared appropriately.

It is as much about attitudes and behaviours with all personnel having the aligned view of what project success means. A collaborative project contract will have personnel working together to solve issues and to reduce cost.

The toolkit explained

Watch William Lindsay and Nicky Mason explain the steps of the Project Collaboration Toolkit.

The Project Collaboration Toolkit model

Project Collaboration Toolkit – Review Checklists

Monitor the progress of your project using the Project Collaboration Toolkit review checklists for Phases 1, 2 & 3 (to print).

Project Collaboration Toolkit in action

The Project Collaboration Toolkit was created to help the UK industry improve its efficiency in a competitive global market by sharing skills and expertise to keep costs down. The following case studies demonstrate how the toolkit is working in practice.

Project collaboration as a catalyst for change: the view from industry

Full profile details

William Lindsay

William Lindsay

Overcoming resistance to collaborative project delivery: managing naysayers

Historical project and contracting practices can hamper progress in creating a collaborative approach to project delivery. Overcoming these barriers and resistance is vital to achieving collaborative project delivery.

Not everyone ‘gets’ collaboration. Many organisations, and the people within them, still hold a ‘win – lose’ view, believing that they can only ‘win’ if someone else ‘loses’.

Think of available project benefits as being analogous to a pie. The traditional approach to project delivery has all parties competing for the biggest slice of the pie that they can get. If someone takes a larger slice of the pie, only they will benefit to the detriment of others. Some contributors may not get a piece at all.

By contrast, project collaboration can be considered as working together to make the whole pie bigger. Whilst the size of the slices may differ, because the overall size of pie has grown, everyone gets an appropriate piece – everyone wins.

Even if business leaders have fully committed to working collaboratively towards an agreed set of common goals, there can be pockets of resistance in some organisational functions and people.

“We need to be aware that in some parts of our industry organisations, particularly larger ones, functions such as legal, procurement and finance can be risk averse. Their natural tendency is to mitigate downside risk.”

This often results in more control, an ‘auditable’ transaction mindset which can stifle innovation. Collaboration encourages organisations to be braver and to grow opportunities. It also recognises that no single organisation can have a monopoly of good ideas. Ideas can be shared more openly once a collaborative environment has been developed and nurtured.

Being open, transparent and supportive of venture partners is counter-intuitive to some people. This is the ‘Build fortification and keep the enemy out’ mindset. But collaboration encourages a mindset of amalgamating available forces and working together.

The traditional approach of transactional project and contracting relationships encourages self-interested behaviour in project parties. In contrast, project collaboration requires behaviours which set aside the self-interests of the businesses and people involved, to collectively pursue the project objectives.

Where is resistance likely to be encountered and how can it be tackled?

Overcoming resistance across internal functions

Some organisations and businesses may have operated very successfully within a traditional project delivery and contracting environment. As a result, some functions or departments may not recognise the need for, and be sceptical of a new approach.

They may believe the traditional approach has served the business well and ‘protected’ it during past times of conflict and adversity.

Particular resistance might be encountered in Legal and Contracts and Purchasing functions, especially if they have been involved in establishing and maintaining a broadly transactional approach to projects.

“When setting up for project collaboration, the focus is understandably on the project team. But time needs to be spent with some of the support functions who may not have the luxury of working on one single project.”

Legal, contracts, procurement, finance and human resources all need to understand what their roles are in enhancing collaboration to maximise benefit.

This old way of doing business is likely to be reflected in processes and procedures designed to protect the organisation in a manner which may be detrimental to others.

It is time to go back to first principles and take a fresh look at how business should be conducted so that it protects the interests of all stakeholders and not just the principal organisation.

To address some of the challenges around collaboration including overcoming resistance and how support functions should be engaged throughout the project, the ECITB developed the Project Collaboration Toolkit. This is available to download along with case studies on how this has been applied in industry.

Overcoming resistance in your people

People who have been in the engineering construction industry for many years are likely to be steeped in the industry culture. They may resist change on the basis of ‘this is the way that it has always been done’.

Key to reducing change resistance within an integrated project delivery team is the selection processes. These need to identify individuals with the right level of emotional intelligence, interpersonal and relationship skills as well as the technical competences needed for the role.

Section 2.1 of the ECITB Project Collaboration Toolkit offers guidance on the considerations for effectively selecting a collaborative team.

What can be done if change resistance is encountered?

It is important to identify and address resistance to change. This is likely to be among those who have always operated using traditional project and contracting practices.

Section 1.1 of the ECITB Project Collaboration Toolkit: appoint a collaboration champion encourages the appointment of suitably influential project leadership who can address the internal change resistance.

This section also discusses how project delivery stakeholder organisations should assess their collaborative capability status and share the findings with their collaborative partners.

As part of this assessment, it may be useful for the delivery stakeholders to assess their conflict handling modes. Tools such as the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument can be useful for this.

To achieve a rapid resolution it is useful to understand how participating organisations are likely to respond to potential disputes and conflicts when the project is in progress.

The toolkit recommends a regular review of project behaviour, as measured against an agreed Project Behavioural Charter. Any breaches of the charter or transgressions, through incidents of expressed self-interest for example, can then be quickly addressed.

“Understanding why teams and functional areas are resistant to change is the first step to implementing collaborative project delivery.”

Setting out principles in terms of a charter that all partners sign up to and putting the right team in place to deliver it will help to reduce self-interest and ensure all parties are collectively pursuing joint project objectives.

“Many Project professionals have been involved in challenging Projects where enormous effort to (re)build relationships has been required. Investing time upfront to engage the naysayers and provide focus on creating a collaborative environment across all parties is always time well spent.”

About William Lindsay

William is Civil Engineer and chartered project professional having completed 30+ years with Shell.

He has been involved with many types of capital project both on and offshore, in the UK and abroad. William spent a year seconded into the Oil & Gas Regulator (now NSTA) in 2016 and was Project Director of the Brent Decommissioning Project in the North Sea, transitioning the organisation through late life operations to down-manning, removal and disposal. This delivered double digit efficiencies for every platform removed having created a successful collaborative environment.

William has recently been the programme delivery director overseeing nuclear decommissioning at Dounreay.

William has been Chair of the Oil & Gas Project Managers Steering Group supporting ECITB to enhance competence of project professionals and promote improved collaboration with the supply chain.

Tony Maplesden

Tony Maplesden

The psychology of project team behaviour

There are a number of areas of potential difficulty associated with establishing an effective project collaboration.

Industry and organisational cultures, based on past practices and experience, can cause resistance to the change from traditional to collaborative delivery strategies.

Quite apart from individual self-interests, there are a number of psychological reasons why people often feel more comfortable in dealing with conflict rather than taking what they perceive as a risk in placing their trust in others.

Why are people resistant to change?

Our first experience in conflict is often during childhood with siblings and extended social networks. Many such sibling rivalries are often just battles for parental attention.

In his book I Don’t Agree, Michael Brown draws on research which indicates that by age 16 we have often experienced a staggering number (counted in thousands!) of sibling and social disputes – 90% of which do not get resolved and 60% result in the total submission of one party to the other.

He also notes that single children are often at a disadvantage in terms of negotiating skills later in life. It is hardly surprising then that some people will revert to the ‘well practised’ ground of conflict in working relationships later in life.

Walter Cannon in the 1920s first described a theory of the ‘fight or flight’ response (aka acute stress response) in animals.

Humans in the modern world are rarely life threatened but in circumstances of extreme stress, will often show a ‘fight’ response.

In the world of work, if people are faced with circumstances that represent a challenge to their interests or threaten their deep-rooted personal values and beliefs, the ‘fight’ response may quite often result in interpersonal conflict.

“In the world of work, if people are faced with circumstances that represent a challenge to their interests or threaten their deep-rooted personal values and beliefs, the ‘fight’ response may quite often result in interpersonal conflict.”

What can be done to change this?

The key to breaking down these barriers is to foster greater diversity.

Gender diversity

In his book, Michael Brown refers to research suggesting that a ‘fight or flight’ response may be genetically locked in human males – having evolved from prehistoric threat experiences.

But the genetic coding of female humans promotes a modified response in circumstances of threat and heightened stress which can be thought of as ‘tend and befriend’. Again, this comes from the evolutionary response to protect offspring.

“A team which has a healthy gender balance is more likely to cope with occasional disputes and conflicts leading to more harmonious internal and external relationships.”

Social and cultural group diversity

Throughout the industrial age in the western world, engineering construction project delivery teams have been composed mainly of western males.

“Flawed project team selection processes, incorporating confirmation and affinity biases, have historically returned stereotypically similar adversarial and group-think behaviours in team members.”

There was rarely any attempt to establish collaboration between organisations and their teams. This promotes self-interested thinking with differentiated objectives being pursued by those involved.

Different geographical, national and social cultures and groups operate quite different beliefs and values to those exhibited by western cultures. Many are more motivated to pursue the common good and the wellbeing of the group rather than to concentrate their efforts on self-interest.

Cognitive and age diversity

With the significant challenges currently facing the engineering construction sector we need to seek new approaches and more effective ways to do things. Now is the time to discard the ‘play book’ and creatively look for alternative solutions.

If we continue to assemble project teams that consist predominantly of engineers or with the majority of members who have a significant period of experience in the engineering construction sector, we are likely to be constrained by convergent thinking.

Project solutions will continue along the lines of ‘the way we have always done things’ and we will ultimately fail to deliver.

To foster an environment of divergent, creative thinking we need to build teams that have varied skills, knowledge and experiences. We need to recruit people from other sectors and backgrounds and a blend of experience.

It is likely to be the younger people in the team, who are not constrained by the experiences of the past, who will be able to spark the creative thinking that is needed.

In summary

Understanding behavioural differences and benefits is key. Project delivery teams with healthy gender, cultural, social group, cognitive and age diversity may be more open to integrated, collaborative working and avoid adversarial behaviours.

Team selection processes are clearly important but integrated, collaborative project delivery teams also need to be supported through their development and as they identify and commit to aligned project goals.

Rather than years of engineering construction industry experience being the core focus in recruitment, we need to prioritise building a diverse team – one that can think creatively, address issues and collectively solve problems rather than falling back on the mantra of ‘that’s how things are always done’.

About Tony Maplesden

Tony is a chartered engineer with over 40 years of experience in the delivery of engineering construction projects. His experience in the process industries has encompassed project assignments ranging from minor ‘works-based’ project programmes to multi-million GB pound capital investment projects.

A fellow of the Association for Project Management (APM), the Institution of Mechanical Engineers and the Institute of Leadership & Management, he has a qualification in management psychology and is a qualified management coach/mentor.

Now semi-retired, during his career he has worked in many senior management roles and delivered projects in a number of industry sectors.

In the final stage of his career, he worked in the UK Oil & Gas industry based in Aberdeen, during which time he held the positions of Offshore Regional Chair and Chairman of the Project Management Steering Group with the Engineering Construction Industry Training Board (ECITB).

During 2016 he played a significant role in the design and development of the ECITB Project Collaboration Toolkit and drafted much of the Toolkit content. He has since been coordinating work associated with piloting of the Toolkit and is presently supporting its application to major projects across a number of UK industry sectors

Author: Tony Maplesden BSc CEng FIMechE FAPM FInstLM

References: I Don’t Agree, Michael Brown, ISBN 978-0-85719-765-8

Addressing the Skills Gap conference

Addressing the Skills Gap conference

Collaboration, competence assurance and digital skills vital for UK water industry

Collaboration, competence assurance and digital skills all came out as key factors for a successful water industry at British Water’s ‘Addressing the Skills Gap’ conference at Cranfield University.

Andy Brown, Chief Operating Officer at the ECITB, chaired the Training & Development Panel at the event.

He said: “The challenges facing the water industry reflect those seen right across the engineering construction industry. It is essential sectors do not work in silos but rather seek to collaborate to help alleviate some of the workforce issues that we are facing.

“The industry is facing real challenges with framework contractors clashing with water companies over delayed or cancelled capital projects. The Project Collaboration Toolkit, collaborative working agreements and collaborative skills training would bring tangible benefits to the water industry.”

The panel discussed the benefits of competence assurance. The panel agreed that ensuring workers have common technical skills and competencies supports workforce agility and resilience by enabling contractors to work across sectors. It can also help alleviate cash flow problems associated with water companies scheduling project work to the end of the asset management plan five-year cycle.

On skills Andy added: “Digital skills are fundamental for those involved in water sector asset management. The ability to analyse data from a variety of sources including digital twins, remote sensor monitoring and drone technology will be key to creating the necessary efficiencies within the sector.”

The conference looked at Building the Talent Pool for Now and the Future in the first of a two-part series. Part two (date to be announced) will explore how well the industry has progressed against its actions and look at what more needs to be done collaboratively across the sector to amplify impact.

Lila Thompson CEO at British Water said: “British Water is delighted to have delivered its first Addressing the Skills Gaps conference in partnership with Cranfield University and supported by the Chartered Institute of Water and Environmental Management (CIWEM) and the Institute of Water.

“There is an urgent need to address the skills gap. With 20% of professionals due to retire over the next two decades, there is a significant opportunity to capture their knowledge to upskill staff, attract a diverse range of talent (including people from neuro diverse and black and minority ethnic backgrounds) and narrate the fact that water sits at the heart of climate change.

“The latter alone should significantly help to attract talent keen to find solutions to tackle impacts of increasing weather volatility and to improve environmental performance.”

Other panel members who spoke at the event included Darren Eckford, Director of Learning and Development at CIWEM; Donna Davies, Digital Skills & Education Lead at Skewb Ltd; Martyn Johnson, ECITB’s Head of Strategic Engagement South & Wales; Tony Maplesden, author of ECITB’s Project Collaboration Toolkit and Guy Hazlehurst, Director at the National College for Nuclear and EDF’s Workforce Development Lead for Sizewell C.

British Water is the water industry’s main trade association. The conference was attended by water companies, contractors, and trade associations.

Read more on British Water addressing the Skills Gap Conference

The Project Management Steering Group (PMSG)

The Project Management activities of the ECITB are led and supported by the Project Management Steering Group (PMSG), a voluntary team which was formed at the request of Industry in 2014. The PMSG works to encourage co-operation between businesses and organises conferences for industry to improve collaborative working.

Sign up for updates

Your information will be used to subscribe you to our e-newsletter.

For more information, please see our Privacy Notice.